Artist Unknown

Kente Cloth, a type of silk and cotton fabric made of interwoven cloth strips native to Ghana, is my favorite African textile. The largest Kente on display was a gift from a graduate student from Cote d’Ivoire, West Africa, whom my wife, Beth, mentored about twenty years ago. This Kente is a very precious gift, as it once belonged to the student’s grandfather.

The Kente can be worn as a wrap, although it is quite difficult to do so for long periods of time, due to the weight of the material. In all my years I have not encountered a better example of Kente.

The second Kente was also a gift, one given to me by Kate Schachter, a Peace Corp. volunteer in Ghana, West Africa. Most Kente Cloths originate in Ghana and thus are often the most delicate and well-made.

Robino Ntila

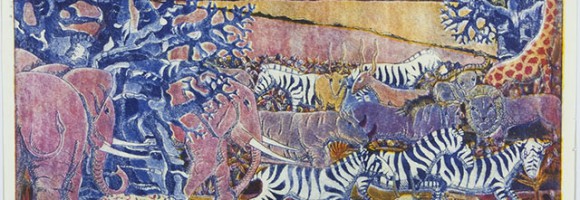

Robino Ntila is an artist based in Tanzania. He works with artists all over Africa, conducting printmaking workshops, mostly with the support of the Ford Foundation. He has taught many artists how to print, helping them market their work in the process.

Robino worked closely with the famous Makonde artist George Lilanga, teaching him the art of printing. Lilanga, one of the few early carvers able to transition from three-dimensional to two-dimensional work, made the transition from carver to visual artist in a movement called Tinga Tinga. His distinct style characterized the start of the movement in Tanzania, one which Ntila continues today, alongside Lilanga’s son.

I met Robino Ntila in Nairobi in 1994. I have more than one hundred Ntila prints, as the artist used to send them to me once a year. Today, Ntila has taken to painting, and thus no longer sends me etchings.

Artist Unknown

These two bone carvings were made by the Maasai ethnic group in Kenya. I purchased them at the Maasai Market in Nairobi. The Maasai are pastoralists and, as such, do not waste any part of their cows, including the bones.

The first bone carving is called a rungu and is used for protection. Most Maasai carry a wooden version of this carving. However, this bone rungu is mostly ceremonial. It is a decorated type of rungu made for tourists and depicts the highly skilled bead work that Maasai women are known for.

The second bone carving is a popular tool with a variety of purposes, one being a smoking pipe. It can also be utilized to stretch and mold leather.

A photographer named Peter Beard published a book titled The Art of the Maasai, in 1992. The book popularized the Maasai bone carvings and by 1994, when I purchased these two, there were few left in the markets. Today, bone carvings such as these demand high prices and are seen mostly in museums.

Peter Beard’s book can be found at the Promega library.

Arthur Tress

These three photographs are very recent acquisitions from an auction in Scottsdale, Arizona. When I came across these images about one month ago, I recognized them immediately for their characteristic surrealistic quality. The value of these photographs far exceeds what I paid for them and I feel honored to have such exceptional items in my collection.

Arthur Tress, a unique and well-known artist, was one of the first in the 1970s to break from street photography and to develop a more personal vision. Tress’s works display a known sudo-realistic, homoerotic facet. He is known for manipulating the reality in front of him, instead of simply being a passive observer.

Arthur Tress’s work can be found in numerous museums and institutions, including the New York Museum of Modern Art, the New York Metropolitan Museum, the George Eastman House, the Bibliotheque Nationale, the Centre Georges Pompidou, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the San Francisco Museum of Art, the Houston Museum of Fine Art, the Whitney Museum of Art, the Stedelijk Museum, the High Museum of Art, the Chicago Center for Contemporary Art, the Cincinnati Art Museum, the Art Institute of Chicago and the Milwaukee Art Museum.

For more information about Arthur Tress, click here.

Arthur Tress

These three photographs are very recent acquisitions from an auction in Scottsdale, Arizona. When I came across these images about one month ago, I recognized them immediately for their characteristic surrealistic quality. The value of these photographs far exceeds what I paid for them and I feel honored to have such exceptional items in my collection.

Arthur Tress, a unique and well-known artist, was one of the first in the 1970s to break from street photography and to develop a more personal vision. Tress’s works display a known sudo-realistic, homoerotic facet. He is known for manipulating the reality in front of him, instead of simply being a passive observer.

Arthur Tress’s work can be found in numerous museums and institutions, including the New York Museum of Modern Art, the New York Metropolitan Museum, the George Eastman House, the Bibliotheque Nationale, the Centre Georges Pompidou, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the San Francisco Museum of Art, the Houston Museum of Fine Art, the Whitney Museum of Art, the Stedelijk Museum, the High Museum of Art, the Chicago Center for Contemporary Art, the Cincinnati Art Museum, the Art Institute of Chicago and the Milwaukee Art Museum.

For more information about Arthur Tress, click here.

Artists Unknown

I purchased this collection of neck rests during my time in Kenya, in the mid-nineties. Every Tuesday I would see a variety of neck rests at an open city market in Nairobi, called the Massai Market. Although this market was mostly comprised of crafts made and sold by Massai women, people sold a large assortment of items brought in from rural Kenya.

Seeing these unique items sparked my collector’s interest and I made it my goal to find varieties and designs from different tribes. Back then I could have easily filled a shipping container with this collection. However, these seem to be becoming rare, as I did not see many during my most recent visit to East Africa.

Artist Unknown

These items make up a collection of Makonde Ebony Wood carvings from Tanzania. These figures date back to the 1970s or later and are of better quality than many I’ve seen during my visits to East Africa.

This specific carving tradition, native to Southern Africa, is distinguishable from most art found in West Africa. The material of choice, African Blackwood (or Mpingo), allows artists to achieve the incredible detail typical of their work. This art is both traditional and contemporary, reflecting a tribal past as well as modern response to urban life. Makonde artists utilize tribal myths and stories as inspiration for their masterful work. Animal statuettes and human or demon-faced ceremonial masks are common.

Mpingo from Tanzania can show up as raw material or finished carving in the large and affluent Nairobi, Kenya tourist market. As these carving skills reached Kenya, they fostered the “Airport Art” of animals, masks and human figures. Additionally, Makonde carvers inspired the TingaTinga movement seen mostly in paintings and prints. For more information, click here.

Francis X. Nnaggenda

These paintings by Francis Nnaggenda are very significant to the arts program at Promega Corporation. The largest painting belonged to the original collection of about 60 paintings I brought from Kenya in 1995. The showing of these paintings, in addition to the large wooden sculpture of mother and child in the Promega BTC atrium, comprised the first exhibition I curated at the BTC.

The painting on canvas was created in response to the larger of the two. Many years ago, I bought and hand-delivered a roll of fine canvas, paints and brushes to Nnaggenda, in Uganda. I wanted to assure this painting could be created with the best materials, as they are hard to find in Africa. My hope is to sell this painting and send money back to Nnaggenda. The third, smaller, painting was a gift from the artist. Although this painting is very small it has “size.”

The mother and child wood carving located in the BTC Atrium originated from a tree culled from the woods near the North Promega Building in 1995. That year, we cut down a black walnut tree, placed it in my Ford F150 and drove it to Nnaggenda at Indiana University at South Bend (IUSB). He carved it there during his artist in residence, which I arranged. It took five weeks to complete and was on display at the IUSB Gallery for one day, after which it was returned here, where it has been on display since.

Daniel Swadener

This photograph of Frank Lloyd Wright is the first photo I purchased from Pedro Guerrero after meeting him in 2002, at his home in Florence, Arizona. Shortly after moving to Arizona, I knocked on his door and we became good friends.

It wasn’t until 2008 that I was able to exhibit the first retrospective of the photos of Pedro Guerrero at Promega Corporation. We celebrated Pedro’s 91st birthday at the reception, with at least 600 admirers in attendance.

In 2009, we exhibited the carvings of Tom Schlanker at Promega. I commissioned Tom to do a relief of Frank Lloyd Wright based on Pedro’s photo and took the carving to Pedro on my next visit to Florence, Arizona. I told Pedro he would either love the carving or sue me for copyright infringement.

As you can see from my photo of Pedro, he indeed liked Tom’s work and posed beneath his copy of the same photo at his home. I’m unsure if he consciously posed the way Wright did in the photo, but Pedro did happen to be wearing a fedora that day.

Honoring Pedro Guerrero was my proudest moment as a curator. Since his passing last year, one week after his 95th birthday, I have missed my friend and cherished our friendship.

Pedro Guerrero

This photograph of Frank Lloyd Wright is the first photo I purchased from Pedro Guerrero after meeting him in 2002, at his home in Florence, Arizona. Shortly after moving to Arizona, I knocked on his door and we became good friends.

It wasn’t until 2008 that I was able to exhibit the first retrospective of the photos of Pedro Guerrero at Promega Corporation. We celebrated Pedro’s 91st birthday at the reception, with at least 600 admirers in attendance.

In 2009, we exhibited the carvings of Tom Schlanker at Promega. I commissioned Tom to do a relief of Frank Lloyd Wright based on Pedro’s photo and took the carving to Pedro on my next visit to Florence, Arizona. I told Pedro he would either love the carving or sue me for copyright infringement.

As you can see from my photo of Pedro, he indeed liked Tom’s work and posed beneath his copy of the same photo at his home. I’m unsure if he consciously posed the way Wright did in the photo, but Pedro did happen to be wearing a fedora that day.

Honoring Pedro Guerrero was my proudest moment as a curator. Since his passing last year, one week after his 95th birthday, I have missed my friend and cherished our friendship.